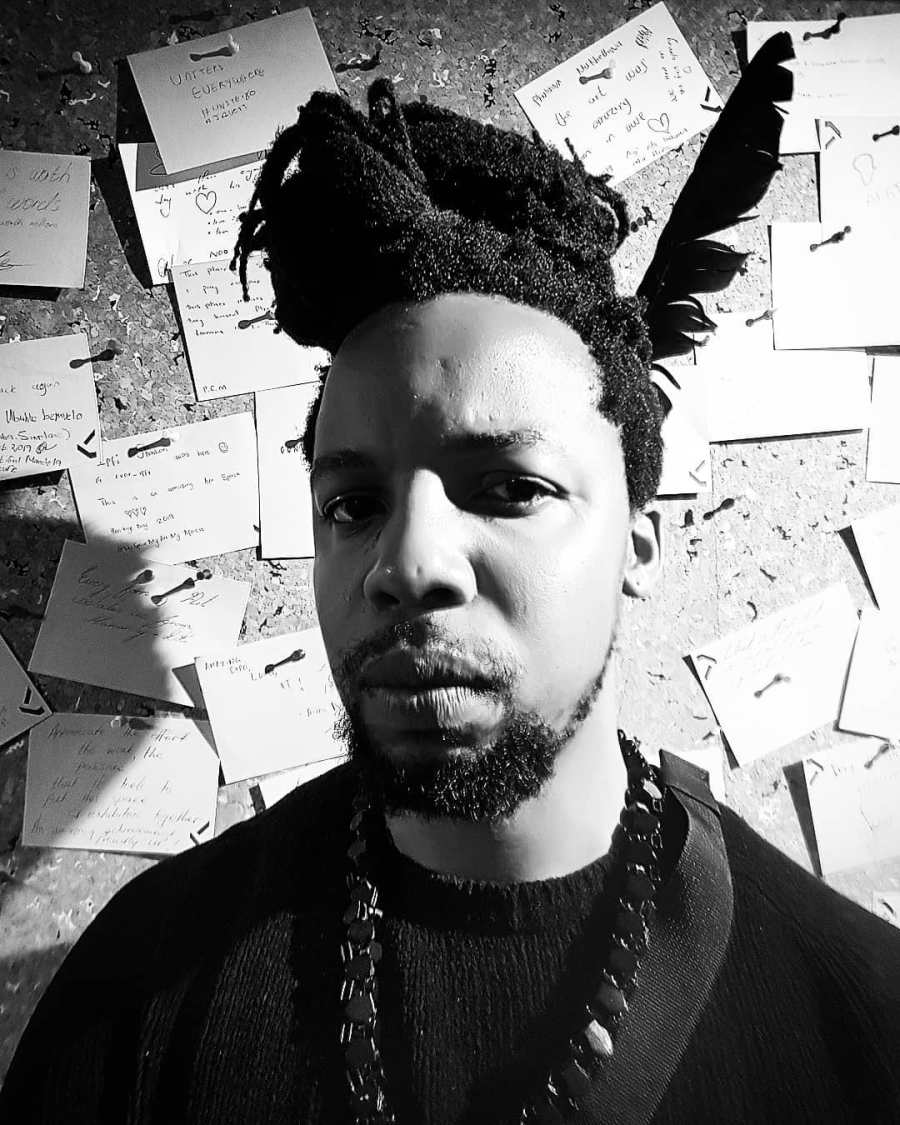

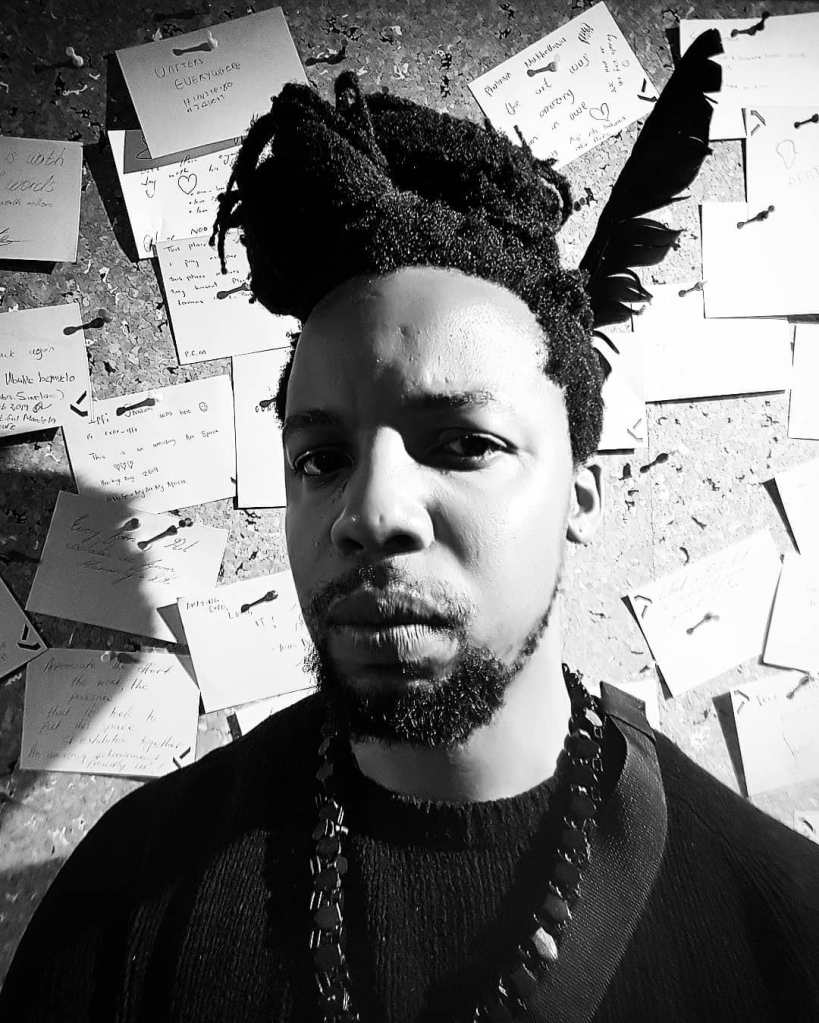

Critically acclaimed South African interdisciplinary artist, designer, and fashion practitioner Lesiba Mabitsela is a changemaker who has received recognition for his contribution to the documentation of sustainable practices in art and design. As a multi-skilled visual artist, he incorporates costume, video, photography, and performance into his work, using his background in fashion design to explore notions of Cultural Capital found in the relationship between post-colonial perceptions of ‘blackness’, gender, religion, and symbolic underpinnings of Western beauty and aesthetics. He has also been named one of Vogue’s Business Innovators: Next-Gen entrepreneurs and agitators for 2023.

After attending his recent exhibition, Bark//Please, in Johannesburg, we knew that we had to engage the mind of the unapologetic and unassuming Creative who is making his mark in the international art scene. Lesiba is the co-founder of the African Fashion Research Institute and director of Lesiba Mabitsela Studio, a made-to-order luxury clothing brand and creative studio established to produce transdisciplinary projects by exploring African fashion histories & identities through a practice that is underpinned by critical fashion & performance studies & an interest in immersive technology. Lesiba is a member of the Einstein Circle on Fashioning Education & a former recipient of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation scholarship, contributing to the completion of his studies in theatre & performance under the guidance of the Institute for Creative Arts (ICA). In October 2021, Lesiba’s article “Reinstitute: Performing methods of undress, má and decolonial aestheSis” was featured in Andy Reilly’s Journal; Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, Volume 8, Issue 1-2: ‘Globalizing Men’s Style’ ‘Sustainability and Men’s Fashion’. Lesiba has worked with The British Council and The Turbine Art Fair and is a thought leader, having recently spoken at the De-fashioning Education conference in Berlin. In his own words, we discuss the decolonization of African luxury and his sustainable practices, which have led him to forge a new path.

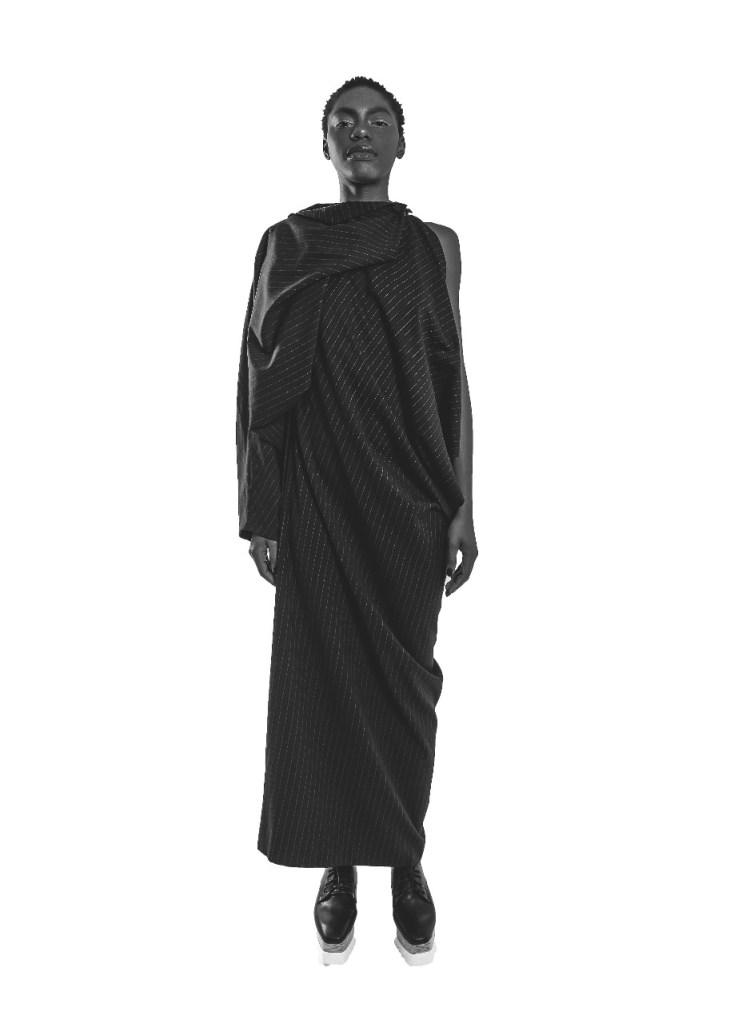

Photo: An ensemble from Lesiba Mabitsela Studio surrounded by pieces from Haider Ackermann, Comme des Garcons, Rick Owens and Jean Paul Gaultier at the Fashioning Masculinities Exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Photographer: Mandla Shonhiwa

Take us through your journey as an artist and designer.

My interest in art & later design started early, following the influence of the American soap opera The Bold & the Beautiful, which I would watch with my mother when I was around the ages of 6 or 7. I had also started drawing as a hobby during those early years; usually, drawings of horses, well-known architectural buildings, and women from magazines. Things became more serious as time went by, especially when I attempted to cut my clothing designs out of cloth used for ironing clothes and cleaning rags.

I took a career in design a lot more seriously in grade 10 when I still had dreams of becoming an architect. Unfortunately, the school dropped woodwork, which was the only subject with professional technical drawing/drafting. Following my interests in school sports, skateboarding, and excelling in art at school, I decided to pursue fashion design following a visit to Tshwane University of Technology, where I ended up obtaining my bachelor’s degree in Fashion Design and Technology.

After a short but valuable period as a Junior Designer for St. Lorient Fashion and Art Gallery in Pretoria, I decided to move to Cape Town to surround myself with the country’s best arts and design talents. Luckily, my first introduction to this world was through the two and a half years I worked for renowned designer Gavin Rajah, whom I had always wanted to work for since I started studying fashion design.

Cape Town was a melting pot for so many creative thinkers and practitioners from all over the African continent and other parts of the world, and I became friends with some very talented individuals but mostly artists for some reason, which was a trend that followed on with me from university. It was probably no surprise then that I got involved in making artwork from the skills I already possessed as a fashion designer, specifically performance art. This allowed me to collaborate with other artists through costumes that I initially made from prison blankets, specifically for the exhibition “Demonstrations: Performing Being Black,” curated by award-winning visual artist and current curator of the Liverpool Biennale, Khanyisile Mbongwa. The importance of performance art is that the discipline uses the body as a canvas, which appealed to the fashion designer in me. I was also able to exercise my conceptual brain, which the industry of commercial fashion design rarely allowed.

Following two years as a relatively self-taught artist, having taken part in platforms such as Infecting the City and The Vrystaat Kunstefees, all while developing a distinct design practice at the same time, having exhibited my work at Design Indaba in 2014, I decided to go back to school and study again, finishing my MA in Theatre and Performance at UCT, where I was co-supervised by renowned curator and choreographer Jay Pather. I have since exhibited a few more performances, taking my work to the Netherlands for the Afrovibes Festival in 2018 and recently staging a commissioned 24-hour durational performance for the UCT Works of Art Collection. My design work has taken a similar trajectory, with two acquisitions of my work following their inclusion in two exhibitions, “Voices of Fashion” and the “Fashioning Masculinities” exhibition at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht and the V&A in London respectively.

Aside from my work in design and the arts, I am also involved in fashion research and education, having established the African Fashion Research Institute (AFRI) with my business partner Dr. Erica de Greef in 2019. The institution is built on three pillars: to develop and promote decolonial fashion education on and for the African continent, to develop accessible avenues to engage with this research through digital platforms, and then to nurture diverse fashion voices on the African continent and its diaspora through transdisciplinary fashion research and education. We regularly give lectures at Central Saint Martins School of the Arts and the Royal College of Arts in London and have recently been getting a lot of attention locally and abroad, having worked with The British Council, the Turbine Art Fair, and including being named on The Vogue Business 100 Innovators: Next-Gen entrepreneurs and agitators for 2023.

Photo: The Man in the Green Blanket, a site-specific durational performance for Infecting the City 2015. Photographer: Donovan Marais

What does African luxury mean to you and what role does it play in art and design?

To me, African Luxury is a concept that is hard to talk about as we would have to delink the concept of luxury from its colonial interpretation and superficial state of being. We have to understand that our proximity to whiteness or European cultural production is usually how luxury is defined in popular culture when concepts of African luxury are being explored, and I would add, performed in mainstream popular culture.

I don’t think the same top-down, “haves/have-nots'” approach can and should be applied. So maybe at the core of your question is to first define what luxury is at its essence and then determine if this concept applies to the lived experience of Africans. I think that luxury can be encountered in the banality of African lived experiences on the continent, linked to a sense of natural privilege. Our weather, for instance, is a luxury, our vast landscapes, sunsets, and wildlife too. Europeans come here to experience that privilege but then they are also pampered with a superficial concept of luxury game reserves which relies on exoticizing that which could be seen as banal for us.

The same could be said for the arts; that which is banal is captured whether through painting, photography, fashion, or performance. It is then presented as an “exotic other“, contributing towards the superficiality of colonial luxury.

Photo: Selected Garments from Lesiba Mabitsela Studio season 19′. Model: Mariah Mckenzie Make Up: Valerie Ekgebo Photographer: Mandla Shonhiwa

What are your thoughts on how art is valued (commercially and intrinsically) in Africa and do you believe African artists and designers are reaping commercial success in international markets?

There has probably never been a better time for cultural production and cultural producers from the African continent than now. Both in the world of Art and Design, the value and interest in African artists, musicians, fashion designers, architects etc. have gone up. Partially due to the internet and social media, the growth of the black middle class, a black elite, and feel-good stories such as the experiences of youth twenty years after the death of apartheid in 1994 all contribute.

Unfortunately, both the industries of Art and Design have been defined by coloniality and are done so through institutions such as museums, universities and so forth which have also dictated ideas of “good taste“. As mentioned, other spaces such as auction houses and galleries then define art and design as a luxury to be enjoyed by the rich, powerful and famous. This sense of luxury is not natural but superficial and based on one’s wealth or personal network.

Fashioning Masculinities Exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Photographer: Mandla Shonhiwa

Is there a place for sustainable luxury in the market and as a designer, how has this influenced your work?

Sustainable production is currently a luxury market in my opinion. Not many designers can purchase sustainably sourced textiles and neither do they have the human resources to research and cross-check suppliers for ethical production practices. This is still the case with my practice, although I have managed to develop relationships with sustainable fabric merchants that I can trust.

I have had to come up with different strategies to try and be as sustainable as possible and that for me, has been done through creating a minimal waste garment construction technique. I also try my best to use old finishing techniques, such as covered buttons, that help to use up as much leftover fabric from the cutting table as possible.

Based on this pattern construction, my garments are often multifunctional, can fit more than one size group and are not gender specific, which means a client can get more out of my garments and I do not have to produce as much. I also produce most of my work myself, but I know this isn’t sustainable for the growth of the business, so I try my best to not only work with local fabric but also local CMT manufacturers.

Lastly, and like the question around luxury, we also need to define what sustainability is for us on the African continent. I remember a reflection from a well-known Kenyan artist and founding member of The Nest Collective, Sunny Dolat who during an online lecture for the Design Future Lab residency, mentioned that in many African homes, no t-shirt would be thrown away before it had been handed down to siblings or other family members or in the worst case scenario, spent an eternity being reused as a spare pyjama, before retiring as a skroplap. Context is key where sustainability is concerned in this case.

We also have a wealth of indigenous “sustainable” textile production on the continent such as barkcloth, banana fibre, moth silk, indigo dye, and raffia. We just need to invest in taking the time and finances to research and experiment with these fibers to get them ready for the global market before others from abroad do this for us.

Pan-African Research Residency Delegation (Including Lesiba Mabitsela) visiting the Durban Botanical Gardens. Photographer: Paulo Menezes from the Contemporary Archive Project

You have had an interesting journey as both an artist and a designer, what is next for Lesiba Mabitsela?

I am currently working through AFRI to research barkcloth and its possible growth and cultivation in the KwaZulu-Natal region. We plan to visit Uganda next year following a successful research trip in Durban this year to see how the bark from the Mutuba tree becomes cloth. This is, of course, all funding dependent, and we welcome any help towards achieving our immediate goal of securing funding so that we can go and do this valuable research.

As an independent artist, I also look to exhibit snippets of my latest body of work, looking into black masculinities in domestic spaces. The work will be a new approach to my current work by experimenting with banal objects such as furniture for the first time in creating some sculptural pieces. I will be showing this work at The Backroom Studio for Creative Arts in Midrand aka SCAM, which is a part studio part gallery I founded based in Noordwyk, Midrand, away from the usual art centers of Rosebank and Parkhurst.

There are a lot of creatives and cultural leaders from this area, which has its unique history, and so I thought that the community I grew up with could benefit from experiencing a cultural institution such as a gallery. I have been spoiled in this regard with my travels to Cape Town and Europe, and I thought to bring a little bit of that experience back home instead of having to drive 30 to 45 minutes to the closest cultural hubs in Johannesburg and Pretoria.

End.

Photo: Selected Garments from Lesiba Mabitsela Studio season 19′. Model: Mariah Mckenzie Make Up: Valerie Ekgebo Photographer: Mandla Shonhiwa

Explore and engage with Lesiba Mabitsela:

Web: lesibamabitsela.com

IG: @lesibamabitselastudio

Newspaper Article: https://mg.co.za/friday/2020-12-04-picking-up-threads-from-the-cutting-room-floor/

AFRI website: http://www.afri.digital

AFRI IG: @afri_digital

Latest project ‘The Fold’: https://linktr.ee/AFRIDigital